ADOPTION, HERITAGE & SPIRITUAL PATH

Finding Spirit chronicles a deeply personal journey of identity, heritage, and healing, tracing the threads of my life from adoption through the rediscovery of my Native American and ancestral roots. This page weaves together the stories of my birth family, ancestors, and cultural heritage, illuminating the challenges, resilience, and spiritual connections that have shaped me.

The page also addresses the trauma and systemic challenges faced by residential school survivors, exploring the lasting impacts on families and the importance of cultural preservation.Through narrative, imagery, and historical context, this page offers a healing journey that honors my ancestors, celebrates cultural continuity, and provides insight into the resilience and spirit of Native families. Visitors are invited to witness not only my personal journey of self-discovery, but also the broader historical and spiritual legacy of my lineage —a testament to survival, identity, and the enduring strength of heritage.

If you have family information, connections, or questions and would like to reach out, please contact me. Your contributions can help piece together the rich history of our shared heritage and strengthen our understanding of our ancestors’ stories.

Hear My Story: A Read-Aloud

If you want to experience my journey as I lived it, click the link below for a YouTube read-aloud of my story. From my adoption to discovery of my ancestry, to my Two-Spirit journey, sobriety, mental health, and spiritual path listen as I share my story in my own voice. This is more than history or facts—it’s a lived experience, full of resilience, healing, and connection across generations. Join me, and let my story speak to you.

Releasing March 1st 2026!

AND THEN THERE WERE SEVEN

MY ADOPTION STORY

My birth story was nothing short of a miracle. To be able to share it today is something I hold with deep gratitude. The strength and love it took for my parents to choose me and walk this journey with me has shaped everything I am. I was born in August 1995, at just 26 weeks gestation, a tiny 1 pound, 14 ounces, about the weight of a loaf of bread. I entered the world fighting to survive, with methamphetamines, cocaine THC and opiates already in my system, and would spend months in and out of the NICU, undergoing countless procedures and hospitalizations.

Premature birth left me with a chronic lung disease called bronchopulmonary dysplasia and left me with lifelong asthma, the result of underdeveloped lungs and repeated intubation. My body was fragile and had numerous surgeries for a stint dealing with an enlarged heart. I needed constant oxygen, monitors, breathing support, and medical intervention just to stay alive. And while the hospital kept my heart beating, it was love that truly held me here.

At the time, my birth mother was in the midst of her own battles with mental health, addiction, abuse, and the burden of survival in an unsupported world. She had already given birth to two disabled twins 9 months before I was born, while managing life with my birth father, who was both her partner and her supplier. She struggled under the weight of expectations, trauma, and poverty. I was returned to the hospital after an overnight visit because I went into respiratory distress and it became clear that the medical care I needed was more than she could manage. She went to Maryland and fled across the country leaving me in California. In May of 1996, I became legally abandoned and deemed unadoptable because of my medical fragility and I was declared an orphan and was granted a ward of the state.

At the hospital, my mom Eva who worked as a Play Therapist. She began to notice me, visit me, and love me. She held me when no one else could. She made sure I didn’t go without a maternal figure. From taking me for stroller “walks” around the hospital to my Nana’s office two blocks away to rocking me in her arms, she gave me the gift of early safety. That love protected me from developing reactive attachment disorder, something common in children without a secure caregiver. The hospital became home to me, but only because of the people who treated me like I mattered, especially my mom Eva.

After months of navigating the system, I was moved into a foster home with a large family, the Clarks. They taught me sign language to communicate simple needs, more, please, juice and laid the foundation for connection and comfort in a family setting.

On February 6th, 1998, at 2 years old, I was officially adopted by Eva and Shane. And as life would have it, the very next day, my mom learned she was pregnant with my sister Tatum. We settled into a warm neighborhood that became a big, extended family. I grew up surrounded by love, laughter, care, and community.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

FINDING MY BIRTH FAMILY

As I got older, I began to ask, who was I before all this? Where did I come from? What was my story before my story?

As part of my healing, my late aunt gifted me a 23andMe kit in 2017. I assumed I was Latino because of my complexion. But that simple DNA test opened a door that led me to my roots. It revealed that I was Native American from the Anishinaabe, Métis, Sans Arc Lakota and Otomí peoples. Other parts of my ancestry are English, Irish, Scottish, Spanish and Portuguese. Suddenly, the pull I felt toward Indigenous tradition, spirit, song, and land made sense. I had blood memory and the ancestors I didn’t know were calling me home.

Even more shockingly, I learned I wasn’t alone. Just like me, six of my siblings had been born to the same mother, all in the span of five years. Two sets of twins and 5 from same parents. All had been adopted and kept together by Doug and Heidi Hendrix and their two sons. All had finally been separated from the life that hurt them, and pulled into the family that saved them. I reached out to one sibling on Facebook. Then another. Soon, a group chat filled with hearts and nervous emojis and tears reunited all of us who’d been scattered.

In 2021, I traveled to meet my family in Maryland and reconnected with my past in the most unexpected way. Standing in a room with “alternate versions” of me, I saw both pain and perseverance reflected. On this trip I also met my birth mother. It wasn’t simple or what some might expect. But it was human. I felt sadness, empathy, confusion, anger, and grace all at once. I let those truths live side by side because healing is not about having all the answers. It is about connection and finding my puzzle pieces.

The Hendrix Family

(From L to R) Amy, Miranda, Jon, Aaron, Hannah, Charles, and Marissa

The Harris Family

Adoption Day!

Aaron's Adopted Family - The Harris, Avelar, and McGinley Family

Aaron, his birth siblings, niece and birth mother.

The Hendrix Family

MY ANCESTRY AND BREAKING THE CYCLE: MY FAMILY LEGACY

THE SHADOWS OF MY FAMILY

Every family has light and shadow, and mine is no different. While reconnecting with my birth family brought understanding and healing, it also revealed deep generational trauma and cycles of abuse, addiction, violence, sa and silence that were passed down through generations of survival.

This story does not glorify suffering or romanticize pain. The truth is heavy. My birth family carried deep wounds from colonization, poverty, displacement, and the emotional and physical scars that come from trying to survive in a world that never gave them safety or peace.

This is not told for shock or pity, but to show that healing is possible even when the roots run deep. I honor my birth family not by erasing what happened, but by acknowledging that their struggles shaped the person I’ve become, someone who chose to break the cycle, to seek truth and recovery, and to offer healing where pain once lived.

In their story, I see both the damage and the resilience. In their mistakes, I see lessons. In their pain, I see the reason I now choose compassion, boundaries, and light. This journey is about transformation, not perfection.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A CULTURE CARRIED THROUGH BLOOD

I was raised believing I was Latino based on complexion and environment — and that was true in part. My grandmother Georgia Martinez Cortez and many other surnames (1949–1995), born to a line of Mexican-American and Native women in Minnesota and Texas. But when I reclaimed my bloodline, I found something even greater coursing through me: generations of Anishinaabe (Chippewa/Ojibwe), Métis, and Sans Arc Lakota ancestors.

My Native roots run deep through my maternal line — unbroken even through forced displacement, adoption, and assimilation. I am not just "of Indigenous descent." My ancestors walked the land now known as Minnesota, Manitoba, North Dakota, and South Dakota, long before these were states or borders.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

THE DUAL LIVES OF MY GREAT-GRANDMOTHER: GREGORDIA MARTINEZ CORTEZ

One of the most fascinating and complicated stories in my family history revolves around my great-grandmother, Gregordia (also Gregoria) Martinez Cortez Cortes. Official records seem to tell two very different stories about her life, yet both point to the same birth date, November 8, 1895 and death date October 10th, 1935 and all the same paternal and maternal siblings, tying them undeniably to the same woman.

- In Minnesota, USA, she appears as Gregordia Martinez Cortez, born around 1895 in Becker County enrolled into White Earth Nation and passing on October 10, 1935, in Renville, Minnesota.

- In Mexico, records show Gregordia (or Gregoria) Yaxcas/Martinez/Cortes/Cortez/Cano De Martinez, born the same day, November 8, 1895, in Rancho Santa Ana, Tamaulipas, and dying decades later on October 10th, 1935, in Reynosa, Tamaulipas.

At first glance, these records seem contradictory, how could one person exist in two places with different death dates and locations? This duality reflects the complex pressures faced by Native families, migrants, and borderland communities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries:

- Migration and Movement: Families often moved across borders for work, safety, or to maintain cultural ties, creating overlapping records.

- Identity Protection: To preserve tribal affiliation, land rights, or safety, Native families sometimes adapted official documents. Names could shift, alternate ethnicities might be recorded, and death records might reflect circumstances unknown to later generations.

- Record keeping Challenges: Bureaucracies in both the U.S. and Mexico often made errors, duplicated entries, or assigned multiple identities to the same person.

For me, this discrepancy isn’t a confusion to be solved—it’s a window into the resilience and adaptability of my ancestors. My great-grandmother lived in multiple worlds: navigating her Ojibwe heritage in Minnesota while connected to her Mexican roots in Tamaulipas. Her life reminds me that survival wasn’t just about enduring hardships, it was about holding multiple identities with grace, strategy, and spirit.

This dual existence is a theme that has resonated through generations of my family, shaping the way we understand identity, belonging, and ancestral strength. It also underscores one of the central truths of my journey: understanding where I come from means embracing the complexity, contradictions, and sacredness of our family story.

Birth Grandmother Georgia Cortez Martinez

Great Aunt Grace

THE JOURNEY OF MY GREAT-GREAT GRANDMOTHER CORDELIA: FROM PIPESTONE TO LOS ANGELES

My great-great grandmother Cordelia was born on October 7, 1916, in Ponsford, Becker County, Minnesota, on White Earth tribal land. Her life reflects both the hardships and resilience of Indigenous families navigating the pressures of assimilation, displacement, and cultural survival.

Her mother, was listed in the 1893 census as “mixed-blood” and tragically passed away at just 27 years old from tuberculosis. Her father, Joseph “Ne Gon E Gwon” Coleman, carried the legacy of the White Earth Nation, specifically the Pillager Band of Chippewa Indians, which historically relocated to the White Earth Reservation in 1873, increasing the population of landless families who sought to maintain their communities and heritage. He passed away in 1895 both Cordelia and her sister, Cecelia Frances Coleman, were adopted by Maxine M. and Joseph H. M.

As a young girl, Cordelia was sent to Pipestone Indian Training School. These schools were designed to forcibly assimilate Native children, stripping them of their language, culture, and family connections. Children were forbidden from speaking their native languages, practicing traditions, or maintaining contact with their families. Residential school survivors like Cordelia often carried the weight of intergenerational trauma, as the physical, emotional, and cultural wounds were transmitted across generations.

Despite these hardships, Cordelia persevered. Her journey from Pipestone to Los Angeles reflects not only the resilience of one young girl but also the enduring strength of her family, community, and Ojibwe heritage. Cordelia moved to Los Angeles married Daniel Cortez and later remarried and passed away on April 2, 1983, in Los Angeles, California. Her journey from White Earth lands, through the trials of residential schooling, to life in a new home stands as a testament to the enduring spirit of her family and their ability to survive and thrive across generations.

1893 - 1953

1893 - 1953

1893 - 1953

Pipestone Indian Training School

1935-07-06

1893 - 1953

1893 - 1953

Te Ata with young unidentified children at the Pipestone Indian Training School.

1893 - 1953

1893 - 1953

1893 - 1953

Interior view of the Carpenter Shop at the Pipestone Indian Training School, several students at work.

1893 - 1953

1893 - 1953

1893 - 1953

Students and staff posing in front of, behind and inside school bus. United States Indian Service No. 4, Pipestone, Minn.

1893 - 1953

1893 - 1953

1893 - 1953

Interior view of the 4th Grade Classroom, Pipestone Indian Training School. Several students seated in desks, bent over work. Teacher standing in back.

THE SANS ARC LEGACY: PROTECTORS, HEALERS, DIPLOMATS

My 6x Great Grandfather, Kahgahgewegwon, known as Crow Feather, was a respected leader of the Sans Arc Sioux (Itazipcho), one of the smaller bands of the Teton Lakota, born during a period of intense change and conflict in the Northern Plains. His people’s hunting territory stretched from the Black Hills to the Missouri River, lands that were central to their culture, spirituality, and survival. Crow Feather’s leadership extended beyond political or military decisions; he was a spiritual guide, mediator, and keeper of sacred knowledge. He served as a medicine man, entrusted with sacred pipes and ceremonies that guided war councils, seasonal hunts, and tribal governance. Oral histories suggest that Crow Feather’s counsel was sought not only within the Sans Arc but also by neighboring bands such as the Miniconjou and Hunkpapa, who often faced the same pressures from U.S. expansion and internal tribal politics.

A key aspect of his leadership was his marriage into the family of Chief Red Cloud, one of the most celebrated Lakota leaders. Crow Feather married three of Red Cloud’s sisters, creating strong familial alliances that strengthened inter-band relationships and solidified his role in diplomacy and leadership. These unions were not only personal but strategic, embedding Crow Feather’s lineage into a network of influence and guidance across the Lakota nation.

During Crow Feather’s lifetime, the Sans Arc navigated a turbulent era of colonization, treaty negotiations, and territorial encroachment. The band sometimes aligned with factions resisting U.S. forces, which complicated their relationships with government officials, while Crow Feather’s wisdom and spiritual authority allowed him to guide his people through these threats with resilience and foresight.

Crow Feather passed away in 1858, leaving his son, Crow Feather III, to inherit his leadership legacy. His son would later sign the Fort Sully Treaty in 1865, a testament to the ongoing negotiations and survival strategies his father had instilled. Crow Feather’s story is more than historical record, it is a testament to ancestral strength, spiritual responsibility, and the endurance of Indigenous knowledge systems in the face of profound upheaval.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

LEGACY AND ANCESTRAL MEDICINE

Crow Feather’s influence persists through generations, not only in blood but in cultural memory and spiritual inheritance. His teachings, his role as a keeper of sacred ceremonies, and his example of leadership are living medicine for his descendants. For me, learning about Crow Feather is a reminder that resilience, spiritual authority, and responsibility are inherited, and that my path of healing, mediumship, and ceremony is a continuation of the work he began centuries ago.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

THE LEGACY OF MY 5X GREAT GRAND UNCLE RED CLOUD: HISTORY AND BLOOD MEMORY

One of the most profound discoveries on my ancestral journey was learning that I am connected to Chief Red Cloud, a name deeply woven into the story of Native resistance, resilience, and sovereignty. Red Cloud (Mahpiya Luta), born in 1822 near what is now Nebraska, was a respected leader of the Oglala Lakota. He is perhaps most known for what became known as Red Cloud’s War (1866–1868) — the only war in U.S. history that was won outright by a Native nation against the U.S. Army. Red Cloud fought to protect Lakota territory and their way of life as settlers and the U.S. government violated treaties and encroached on sacred land.

He was also instrumental in the negotiation of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which guaranteed the Lakota people possession of the Black Hills — a pledge the United States would later break, continuing a legacy of betrayal and resistance. Red Cloud’s leadership didn’t end on the battlefield. He spent the remainder of his life advocating for the rights and welfare of his people, working to secure food, land, and autonomy for the Lakota during a time of intense cultural assault. He died in 1909, still a firm believer in education, identity, and remembering the old ways even in the face of forced assimilation.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

WHY RED CLOUD MATTERS TO MY HEALING

Learning about Red Cloud was more than discovering a notable ancestor, it was uncovering a legacy of strength and responsibility. To come from a chief who fought not only for land, but for ways of being, storytelling, language, and spiritual life that colonial forces tried to eradicate, means that my work today is not just personal. It is part of a continuum. When I speak for the importance of remembering, when I advocate for Native identity and spirituality, when I teach others to reclaim what was taken, I am echoing the same duty Red Cloud carried. His story reminds me that healing isn't just internal. It's collective.

It’s rooted not only in reclaiming personal identity, but in restoring what was taken from entire generations.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

RED LAKE, WHITE EARTH, AND THE SACRED LINE OF WOMEN

From Crow Feather’s union came John Anindusogwonnayau Indahsogwon Coleman, his son, my Great-Great-Great-Great-Great Grandfather. His daughter-in-law, my sacred ancestor Julia “Kah-Zhah-Kaince” Bassett, was born around 1875 on Red Lake Reservation in Minnesota during a time when boarding schools, allotment policies, and relocation threatened the Anishinaabe/Ojibwe way of life.

Julia’s mother, Caroline Oliver Mindemoyien Kahgwaduck Mindemoein Jourdian (b. 1850, Red Lake Reservation), was born into a Métis-Ojibwe lineage of hunters, river guides, and women who bore children into both the colonial and traditional world. Caroline’s mother, Susanna Maw Kaince Sarah Taylor was born in 1824 in Red River, Manitoba, before the U.S.-Canada border split ancestral land. That is where my Métis roots take form, born of Native women and French fur traders, connected to the Red River, and recorded in the Hudson Bay records long before America drew its lines.

Caroline’s father, Joseph Zuzens Jourdain (b. February 1821), was one of the many children of Jean-Baptiste Jourdain, a documented Métis figure of the Red River Settlement. Some records also reference Jean-Baptiste under names such as Eustache or Weshtash, reflecting the dual naming practices common among Métis and Indigenous families at the time, where European baptismal names and Indigenous or vernacular names coexisted. Jean-Baptiste had multiple families with both Native and French-Canadian partners, linking Ojibwe and European roots across generations.

Joseph’s birth is recorded in the Red River Settlement Register of Baptisms (1820–1841, HBCA E 4/1a), a key archival source documenting the lives of Métis and Indigenous families during the fur trade era. These registers show not only the blending of cultural identities but also the survival and adaptation of families navigating treaty negotiations, colonial pressures, and intermarriage. Joseph’s lineage represents the continuity of Ojibwe and Métis heritage, carrying forward resilience, knowledge, and ancestral memory through generations. Together, this side of my family survived genocide, dislocation, biological attacks, and forced assimilation and still passed on language, kinship, and medicine in their names and memories.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

MIXED BLOOD, MANY NATIONS, ONE SPIRIT

Other ancestral names through time:

- Wahbejeob Wahbunegahbow (1815–1889),

- Ogemah “Chief of Earth” Obequodaince,

- Waymekahnah Waymecumah of Leech Lake,

- Ogemahkewenzie “Big Tobacco,"

- Heȟáka Sápa, commonly known as Black Elk, was a wičháša wakȟáŋ (holy man/medicine man) and heyoka (sacred clown) of the Oglala Lakota and second cousin of the war leader Crazy Horse come up in a few different space holders in my lineage as well through inter tribal marriage and ancestry but have yet to be confirmed.

- And at least 14 generations back: warriors and women named Heaven Fear, NN of Cleveland River, and Ke-che-cos-se-kot, born around 1500 in what is now Quebec and in North Carolina.

Some were forced into Christian names, forging Mexican nationalities as a way of survival and colonial records. Others remained known only by land remembrance. But their strength stayed and I carry every story inside me.

1820 - 1865

1820 - 1865

1820 - 1865

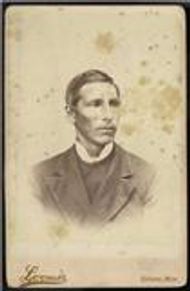

5th great-granduncle Kahgahgewegwon "Crow Feather"

1820-1860

1820 - 1865

1820 - 1865

5th Great Grand Uncle Kadawibida NoKa Gaa-dawaabide Broken Tooth oke “Bear” Breshieu

1774-1864

1820 - 1865

1774-1864

1st cousin 6x removed Original Oglala Sioux head chief. Smoke was a nephew of Red Cloud and an uncle of Crazy Horse.

1840-1877

1840-1877

1774-1864

2nd cousin 6× removed Crazy Horse Worm (Tatanka Maka Gliyuska) of the Sioux Nation

1849-1920

1840-1877

1849-1920

1st cousin 6x removed - John "Aindusogwonnayau Indahsogwon" Coleman

1822-1909

1840-1877

1849-1920

5th Great-Granduncle Maȟpíya Lúta/Red Cloud

MY TWO SPIRIT STORY: TRANSITION, SOBRIETY AND GROWTH

EMBRACING MY TWO SPIRIT IDENTITY

Being Two-Spirit isn’t just about sexual or gender identity in a modern sense, it’s about heritage, spirituality, and purpose. Before colonization, people like me were honored in many tribal nations as balance-keepers, healers, and mediators. We walked between worlds, offering guidance and insight that was both intuitive and ancestral.

I began my social transition at age 16, navigating the complexities of high school while stepping into a truth that many didn’t yet understand. In 2015, I began medical transition with HRT, and by 2019 I had top surgery, affirming my body in ways that mirrored the truth of my spirit. Through this journey, I learned that I don’t fit neatly into Western definitions of gender and that’s because I wasn’t meant to. I am both masculine and feminine, more than a label, occupying two worlds in sacred duality. This understanding shaped not just how I live, but how I heal and serve.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SOBRIETY AND RECLAIMING MY SPIRIT

Sobriety became a cornerstone of my healing. Early adulthood was marked by numbing, disconnection, and avoidance, as I attempted to silence the pain of not knowing myself, unprocessed trauma, and a sense of not belonging. Substances temporarily quieted the storm inside, but they couldn’t heal the deeper wounds. The path to sobriety was emotional, humbling, and transformative. Giving up alcohol and substances wasn’t merely breaking an addiction, it was about reclaiming my body, spirit, and clarity. Sobriety allowed me to face trauma, grief, and pain I had long avoided, making space for joy, presence, connection, and purpose to enter my life.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

NAVIGATING MY MENTAL HEALTH STRUGGLES AND GROWTH

My mental health journey has been intertwined with my Two-Spirit identity and ancestral heritage. I have faced depression, anxiety, dissociation, and layers of trauma, often believing it was my personal failure. Over time, I realized much of my struggle stemmed from inherited trauma: bloodlines marked by genocide, displacement, abuse, and cultural erasure.

Healing my mind required healing my spirit. Therapy, personal ceremonies, community support, and spiritual practices each offered unique tools for understanding, processing, and integrating my experiences. Today, I speak openly about mental health because I know how isolating it can feel and how critical it is to recognize that we are not meant to heal alone.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

WALKING WITH INTENTION AND COMPASSION

I offer healing not as someone removed from pain, but as someone who has learned to walk alongside it with intention, compassion, and truth. My Two-Spirit identity, sobriety, and mental health journey are inseparable parts of who I am, and they inform the work I do as a healer, medium, and guide.

This story is about embracing authenticity, reclaiming ancestral power, and honoring the interconnectedness of spirit, mind, and body. It is an invitation for others to see that healing is possible, and that our struggles can be transformed into sources of wisdom, purpose, and resilience.

My Spiritual & Medicine Path

LINEAGE AS MEDICINE: HOW KNOWING MY ANCESTORS CHANGED MY HEALING

For most of my life, I felt a deep, unexplainable longing I couldn’t name. I grew up as an adoptee with no connection to my biological family, culture, or origins. I was raised with love, but I was also raised with questions: Who am I? Where do I come from? And why do I feel so different from the world around me?

It wasn’t until I began the journey of uncovering my ancestral roots that everything shifted. Learning who my ancestors were didn’t just help me answer those questions. I discovered I wasn’t just adopted into a family; I was descended from a lineage of Chiefs, keepers of tradition, spiritual leaders, land protectors, Métis women, and warriors who survived generations of persecution, loss, and transformation.

All the things I had long felt, my connection to spirit, my spiritual gifts, my sense of not “belonging” in the modern world and suddenly it all made sense. My blood remembered, even when I didn’t.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

HEALING THROUGH KNOWING

The more I learned about my ancestry, the more I realized how much had been taken not just from me, but from generations before me. Stories, languages, identity, belonging… and most of all, connection. But even through displacement and colonization, enough survived to reach me.

My healing didn’t just begin with learning the facts of my heritage; it started when I felt the presence of those who came before me. I realized there was no separation between us that healing could happen through cultural reclamation, spiritual ceremony, and accepting the responsibilities of my bloodline.

Learning who my ancestors were healed me in places I didn’t even know were wounded. Knowing where I come from changed how I see myself but not as broken, but as a continuation of endurance and hope.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

MY SPIRITUAL AND MEDICINE PATH

I began connecting to spirit long before I understood what was happening. As a child, I sensed things beyond the physical world. It wasn’t until adulthood, when I began to learn more about my ancestry, that I understood these gifts were inherited. As I reconnected with the land and with traditional teachings, I found my way into my medicine path, one that is rooted in Indigenous knowledge systems, ceremony, and the role of being a spiritual bridge between realms. I now work as a Medium Spiritual Advisor and a Healer, offering messages and guidance not only for individuals but for communities who have been disconnected from their own cultural or spiritual roots. My purpose is to honor the ways of my people by supporting healing, connection, and cultural resurgence for myself, my ancestors, and my future generations.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

HONORING MY ANCESTORS TODAY

My life today is an act of honoring. I carry feathers and beads not as adornment, but as prayer. I speak my ancestors’ names not to glorify lineage, but to acknowledge inheritance. I know there is so much pain and trauma in my birth family and lost memories and shared connection. The hurt and pain caused was out of fear, abuse, abandonment and lack of love. I don’t claim perfection or status, I claim responsibility. Responsibility to remember. Responsibility to heal. Responsibility to reconnect broken connections so that those who come after me don’t have to start from scratch again. Every message I share, every reading I give, every ceremony I host is done with one intention: to honor the people whose strength is the reason I am still here.

I am accountable and I am still becoming.

PHOTOS FROM MY RESEARCH

6th Great-Granduncle Kahgahgewegwon "Crow Feather"

© 2022-2026 Aaron Harris Live | FIVEONE PRODUCTIONS | All Rights Reserved | Privacy Policy & Disclaimer

❤️ VALENTINE’S MONTH SPECIAL ❤️

All February long, receive 50% OFF your session as a gift to your heart, your healing, and your loved ones in Spirit.

Use code HEART at checkout

Valid all month • Limited availability • Book now 💖

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.